Nonlinear Subspace Cloth Simulation

Author

Qingyang Tan (qytan@cs.umd.edu)

Abstract

In this project, we want to build a cloth simulator in a nonlinear subspace to reduce the search space. We leverage the graph-based convolutional neural network (GCNN) with a physical-inspired loss term to build an embedding network for cloth models. We then use mass-spring systems or finite-element method (FEM) to model the cloth energy and build a simulator based on the nonlinear embedded space. We show that using the proposed method can better capture cloth deformation and generalize on new control information well.

Introduction

Cloth simulation has applications in different areas, including animation, robotic control, gaming. Usually, the cloth is modeled as a 2D thin-shell object in a 3D space and represented by a high-resolution mesh. Many techniques have been developed to simulate the deformation of cloth in this mesh-based representation, including the mass-spring systems [1], the finite-element method [2]. However, the complexity of these methods depends on the number of degrees of freedoms (DOF), vary from $\mathcal{O}(n^{1.5})$ to $\mathcal{O}(n^{3})$. It would be hard to deploy high-resolution cloth simulation on devices with limited computation resources, e.g., cell phones.

Data-driven methods have been proposed to accelerate the simulation process. These kinds of methods leverage the results from pre-computation to accelerate run-time simulation process. Previous works including non-learning methods, such as motion graph [3], and learning-based methods, such as subspace simulation [4, 5] and frame predictor [6, 7]. However, previous methods may suffer from loss of details or freedom of new control information.

In our project, we propose to combine GCNN based neural network embedding [8] and subspace integration to capture more details of cloth deformation while allowing full freedom to control the cloth simulation.

Related Work

We will briefly discuss previous works in this section.

Motion Graph

[3] proposes to incrementally construct a secondary cloth motion to capture almost everything in the system and then compress the raw mesh data from tens of gigabytes to only tens of megabytes. This method allows the system to capture the effect of high-resolution, off-line cloth simulation for a rich space of character motion and deliver it efficiently as part of an interactive application. However, the simulation is fully constrained by pre-computation and it can only deliver results explored during construction. We want to use subspace integration to give users full control of the cloth simulation process.

Subspace Integration

[4, 5] both conduct subspace integration to accelerate model simulation. [4] uses mass-scaled principal component analysis (mass-PCA), which is a linear model. [5] uses a fully-connected autoencoder based on PCA results, which is not computationally efficient and is constrained with the linear PCA basis. Thus, both methods cannot capture the nonlinear deformation well of cloth material. We propose to leverage the power of GCNN to exploit the subspace of cloth models and increase the accuracy of deformation.

Frame Predictor

[6, 7] use machine learning methods to model the simulation process of cloth. Use linear regression or neural network-based method to predict the next frame given control parameters and previous few frames. These methods can be very quick since they do not require heavy computation of the physics model. However, this scheme can easily let the system be overfitted on training data, and it would behave badly on the new unseen control information, as we will show in the result section. So we stick to model the physics law explicitly.

Proposed Method

GCNN-based Embedding

In this section, we provide an overview of low-dimensional embedding of the cloth meshes. Our goal is to obtain a subspace through a set of $N$ deformed cloth meshes, $S_m$, with each mesh represented using a set of $K$ vertices, denoted as $\mathbf{p}_m\in\mathbb{R}^{3K}$.

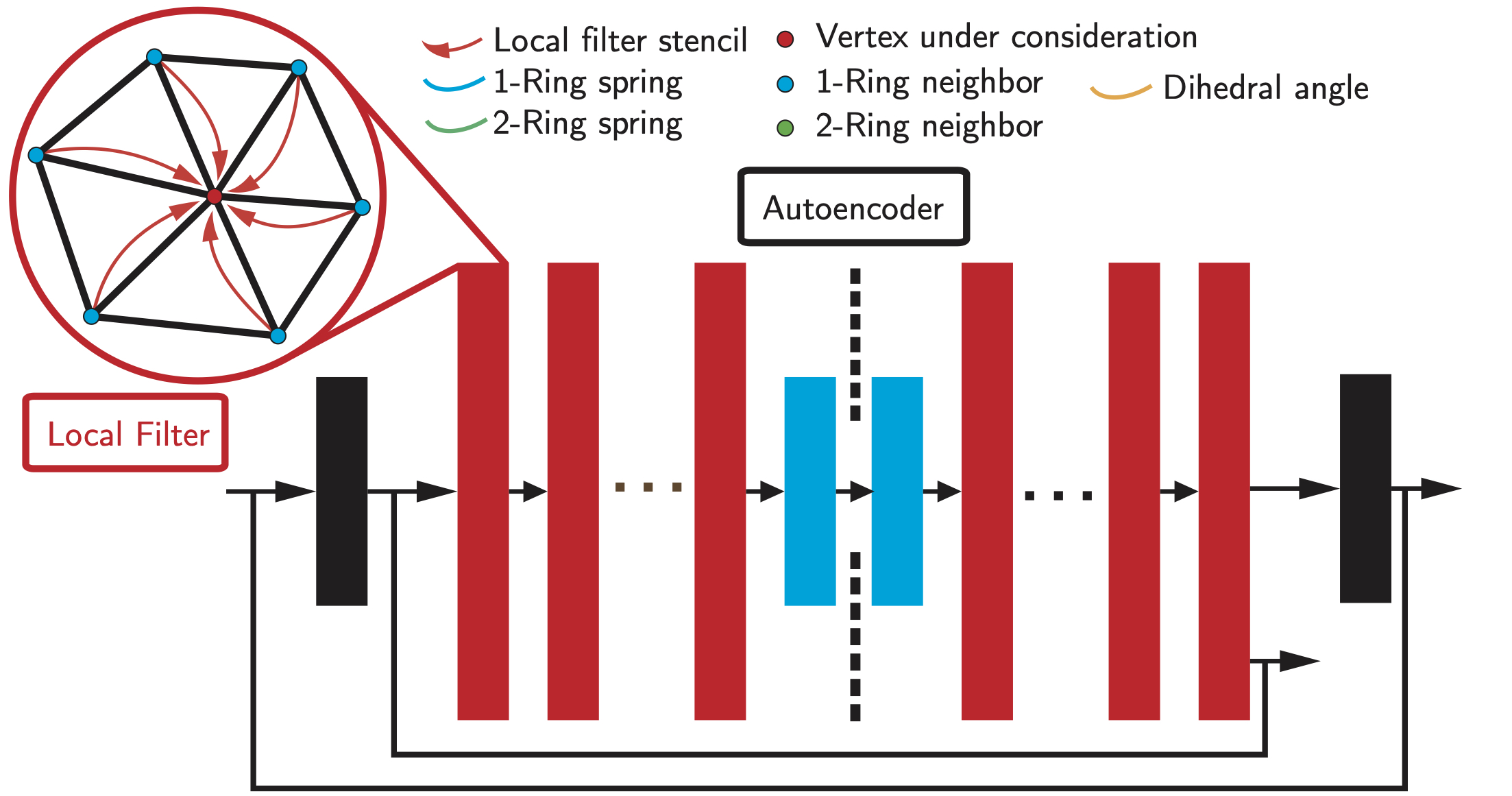

We denote the $i$th vertex as $\mathbf{p}_{m,i}\in\mathbb{R}^3$. Here $m=1,\cdots,N$ and $i=1,\cdots,K$. These vertices are connected by edges, so we can define the 1-ring neighbor set, $\mathcal{N}^1_i$, and the 2-ring neighbor set, $\mathcal{N}^2_i$, for each $\mathbf{p}_i$. Our goal is to find a map $\mathbf{z}\to\mathbf{p}$, where $\mathbf{z}$ is a low-dimensional feature and $\mathbf{p}\in\mathbf{R}^{3K}$ such that, for each $m$, there exists a $\mathbf{z}_m$ where $\mathbf{z}_m$ is mapped to a mesh close to $\mathbf{p}_m$. To define such a function $\mathbf{D}$, we use graph-based CNN and ACAP features [9] to represent large-scale deformations.

We define $\mathbf{D}$ as a graph-based CNN using local filters $$ \mathbf{D}\triangleq\mathbf{C}_L^T\cdots\mathbf{C}_2^T\circ\mathbf{C}_1^T\circ\mathbf{F}^T, $$ where $L$ is the number of convolutional layers and $\mathbf{C}^T$ is the transpose of a graph-based convolutional operator, $\mathbf{F}$ is a fully connected layer. Each layer is appended by a leaky ReLU activation layer.

A graph-based convolutional layer is a linear operator defined as: $$ \mathbf{C}(\mathbf{x})_i = \mathbf{W}\mathbf{x}_i+\mathbf{W_N}(\Sigma_j\mathbf{x}_j)/N_i + b, $$ where $\mathbf{W},\mathbf{W_N}, b$ are optimizable weights and biases, respectively; $j$ is the index of neighbors of $i$ and $N_i$ is the degree of vertex $i$.

The following figure shows the network architecture:

All the weights in the CNN are trained in a self-supervised manner using an autoencoder and a reconstruction loss in ACAP feature and physical-inspired loss mentioned in the later section.

Model the Physics of Cloth Deformation in Subspace

We assumes that cloth sequence could be generated using a physics simulator that solves a continuous-time PDE of the form:

\begin{align}

\mathbf{M}\frac{\partial \mathbf{p}}{\partial t}=-\mathbf{force}(\mathbf{p},\mathbf{q}),

\end{align}

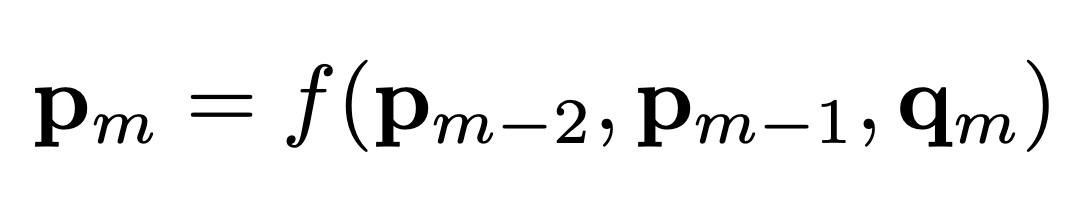

where $\mathbf{M}$ is the mass matrix and $t$ is the time. $\mathbf{force}(\mathbf{p},\mathbf{q})$ models internal and external forces affecting the current mesh $\mathbf{p}$. The force is also a function of the current control parameters $\mathbf{q}$. This continuous-time PDE can be discretized into $N$ timesteps such that $S_m$ is the position of the cloth at time instance $i\Delta t$, where $\Delta t$ is the timestep size. A discrete physics simulator can determine all $\mathbf{p}_m$ given the initial condition $\mathbf{p}_1,\mathbf{p}_2$ and the sequence of control parameters $\mathbf{q}_1,\mathbf{q}_2,\cdots,\mathbf{q}_N$ by the recurrent function:

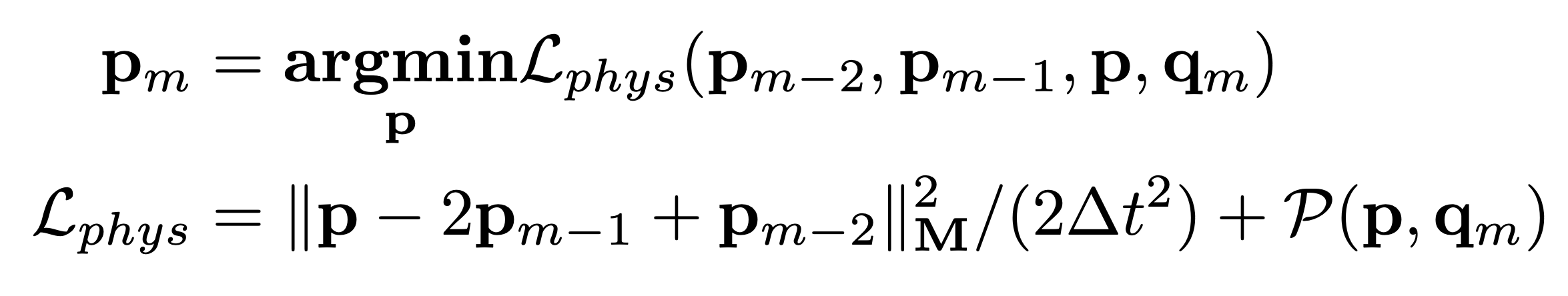

where $f$ is a discretization of the continuous-time PDE. To define this discretization, we reformulates $f$ as the following optimization:

where $f$ is a discretization of the continuous-time PDE. To define this discretization, we reformulates $f$ as the following optimization:

Here the first term models the kinematic energy, which requires each vertex to move in its own velocity as much as possible if no external forces are exerted. The second term models forces caused by various potential energies at configuration $\mathbf{p}$. In this work, we consider three kinds of potential energy:

Here the first term models the kinematic energy, which requires each vertex to move in its own velocity as much as possible if no external forces are exerted. The second term models forces caused by various potential energies at configuration $\mathbf{p}$. In this work, we consider three kinds of potential energy:

- Gravitational energy $\mathcal{P}_g(\mathbf{p})=-\sum_i\mathbf{g}^T\mathbf{M}\mathbf{p}_i$, where $\mathbf{g}$ is the gravitational acceleration vector.

- Stretch resistance energy, $\mathcal{P}_s$, models the potential force induced by stretching the material.

- Bending resistance energy, $\mathcal{P}_b$, models the potential force induced by bending the material.

There are many ways to discretize $\mathcal{P}_s,\mathcal{P}_b$, such as the finite element method used in [2] or the mass-spring model used in [1]. Both formulations are evaluated in this work.

- [1] models the stretch resistance term, $\mathcal{P}_s$, as a set of Hooke’s springs between each vertex and vertices in its 1-ring neighbors. In addition, the bend resistance term, $\mathcal{P}_b$, is defined as another set of Hooke’s springs between each vertex and vertices in its 2-ring neighbors.

- [2] models the stretch resistance term, $\mathcal{P}_s$, as a linear elastic energy resisting the in-plane deformations of each mesh triangle. In addition, the bend resistance term, $\mathcal{P}_b$, is defined as a quadratic penalty term resisting the change of the dihedral angle between any pair of two neighboring triangles.

We use the physical term defined for the optimization problem for training the autoencoder. This should improve the accuracy of the embedded shapes.

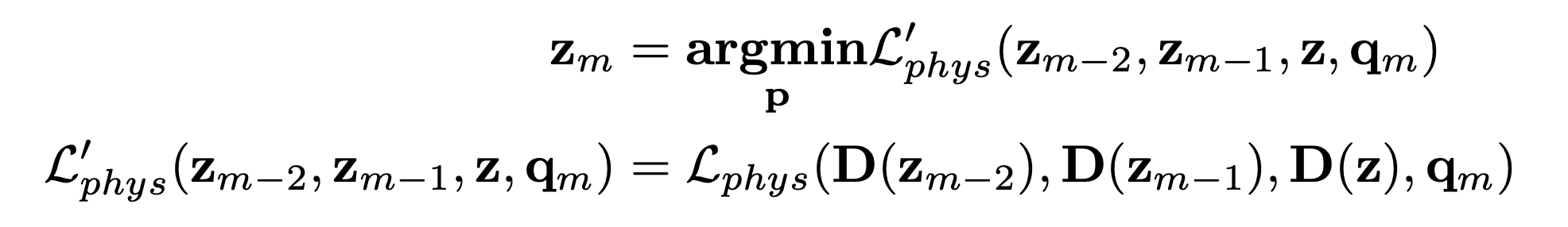

After the training of the autoencoder, we get the subspace of the cloth models, and the mapping $\mathbf{p} = \mathbf{D}(\mathbf{z})$, we can rewrite the optimization problem as

Using the new optimization problem, we can reduce the search space, and accelerate the process of cloth simulation.

Using the new optimization problem, we can reduce the search space, and accelerate the process of cloth simulation.

Implementation

We build the neural network with the TensorFlow package and implemented the mass-spring model and FEM with C++ customized TensorFlow operation. We use the optimization method from the Scipy package to run the cloth simulation. Specifically, we use the L-BGFS-B method.

Experimental Results

Embedding Comparison

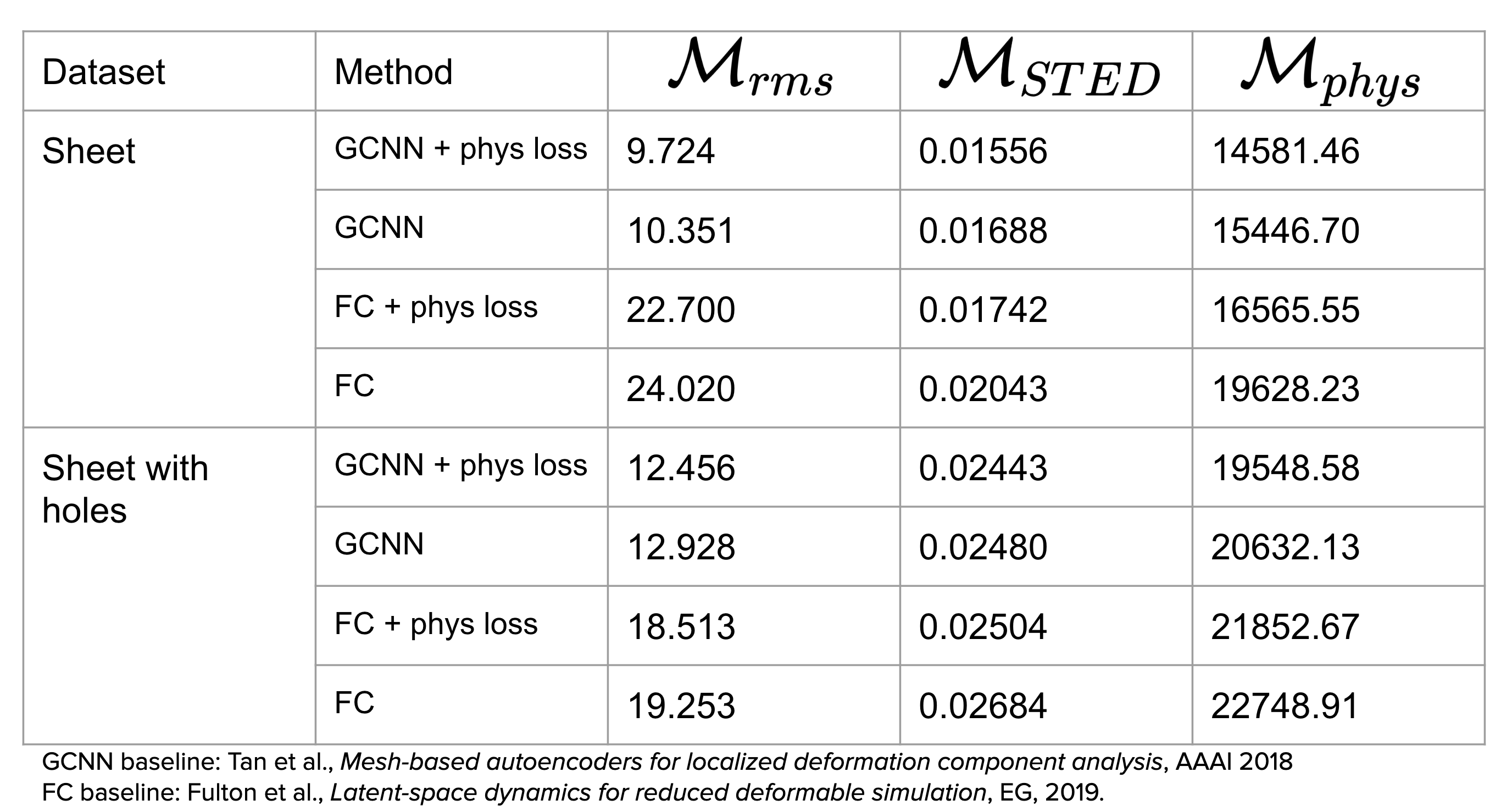

We first compare the reconstruction ability of our subspace with previous methods. In this experiment, we create 2 sequences using [1] with $N=2400$ frames. The first sequence has $K=4224$ vertices with no holes, while the second sequence has $K=4165$ vertices with holes. During the comparison, for each dataset, we select the first 12 frames in every 17 frames to form the training set. The other frames are used as the test set. We compare several metrics: 1) the root mean square error, $\mathcal{M}$rms; 2) the STED metric, $\mathcal{M}$STED, measuring the visual quality; 3) the physical metric, $\mathcal{M}$phys, measuring the norm of partial derivatives of $\mathcal{L}_{phys}$. The results are shown in the following table:

These suggest that our method using GCNN backbone network with physical-inspired loss can better capture the deformation of cloth.

New Control Parameter Comparison

We claim in the previous section that previous methods using frame predictor such as [7] could not generalize on new control parameters well, here we give an example:

The generated sequence is unstable and has clear drawbacks on the four corners.

Meanwhile, since our method directly models the physical terms behind cloth deformation, it can perform well in this situation:

Different Topology

We show an example of cloth with holes:

FEM-based Results

We show an example using FEM to model the potential energy:

Conclusion

In sum, in this project,

- we build a non-linear GCNN-based subspace simulator for cloth deformation;

- we include different physics modeling methods, the mass-spring system, and FEM.

Due to time limitation, the system still has some drawbacks, we want to improve the work in the following ways:

- we want to move full computation to GPU, to accelerate the simulation process;

- we want to use more accurate optimization method, right now we only use a quasi-Newton method;

- we want to add collision detection in the whole pipeline, maybe still through data-driven methods.

References

[1] K.-J. Choi and H.-S. Ko, “Stable but responsive cloth,” in SIGGRAPH 2002.

[2] R. Narain, A. Samii, and J. F. O’Brien, “Adaptive anisotropic remeshing for cloth simulation,” ACM TOG, 2002.

[3] D. Kim, W. Koh, R. Narain, K. Fatahalian, A. Treuille, and J. F. O’Brien, “Near-exhaustive precomputation of secondary cloth effects,” ACM TOG, 2013.

[4] J. Barbič and D. L. James, “Real-time subspace integration for st. venant-kirchhoff deformable models,” ACM TOG, 2005.

[5] L. Fulton, V. Modi, D. Duvenaud, D. I. W. Levin, and A. Jacobson, “Latent-space dynamics for reduced deformable simulation,” Computer Graphics Forum, 2019.

[6] E. De Aguiar, L. Sigal, A. Treuille, and J. K. Hodgins, “Stable spaces for real-time clothing,” ACM TOG, 2010.

[7] D. Holden, B. C. Duong, S. Datta, and D. Nowrouzezahrai, “Subspace neural physics: fast data-driven interactive simulation,” in Proceedings of the 18th annual ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics Symposium on Computer Animation. ACM, 2019.

[8] Q. Tan, Z. Pan, L. Gao, and D. Manocha, “Realtime simulation of thin-shell deformable materials using cnn-based mesh embedding,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.12354, 2019.

[9] L. Gao, Y.-K. Lai, J. Yang, L.-X. Zhang, L. Kobbelt, and S. Xia, “Sparse Data Driven Mesh Deformation,” IEEE TVCG, 2019.